Pink Floyd's Live Stage Set-up

Sound On Stage number 5, March 1997

"Welcome to the Machine - the story of Pink Floyd's live sound: part 1"

Over the 30 years that have passed since their debut record,

Pink Floyd have remained unchallenged as the rock world's

premier live attraction. In this unique and comprehensive

four-part series, MARK CUNNINGHAM traces the development of

the Floyd's live sound and talks to the key personnel who

have contributed to some of the greatest shows on Earth.

When Pink Floyd embarked on their most recent jaunt around the

world with the 1994 Division Bell tour, no less than 53 articulated

trucks were required to transport the PA and lighting systems,

projection equipment, staging, and all the additional elements which

went into what has so far been acclaimed as the benchmark touring

production of the '90s. By contrast, at the time of the band's first

single, "Arnold Layne", in the spring of 1967, they traversed the

country in a humble van.

Given the musical sophistication of their later years, it is

equally difficult to conceive of Pink Floyd as a run-of-the-mill R&B

combo, and yet this is precisely how they began when they were formed

at the Regent Street Polytechnic School of Architecture in 1965 as

The Abdabs by bassist Roger Waters, keyboard player Rick Wright, and

drummer Nick Mason and several others. Like most bands of their time,

their early repertoire consisted mainly of R&B and pop covers, and was

broadened when guitarist, singer, and Bo Diddley fan Roger "Syd"

Barrett arrived in the line-up, conjuring their new name: The Pink

Floyd Sound. Within a year, Barrett blossomed as a songwriter,

producing whimsical numbers such as "Candy And A Currant Bun", which

would steer the band in a new direction.

Soon to drop the redundant suffix (and the definite article),

their live set began to feature extended, feedback-drenched

instrumental "freak-outs", largely dominated by Barrett's guitar

experimentations and Wright's Stockhausen-flavoured organ solos.

Arguably, the biggest influence on the band's development at the

forefront of the psychedelic revolution was Barrett's appetite for

a certain hallucinogenic substance. Musically, however, he relied

heavily on his echo box and slide techniques, often involving ball

bearings, plastic rulers or a Zippo lighter, to achieve his eclectic

blend of guitar effects, while the other band members experimented

with similar flair. You had to be there.

By early 1967, Pink Floyd had secured both an EMI record deal and

an enviable following as the darlings of London's underground scene

with their "free-form", jazz-inspired, psychedelic noodlings,

frequently accompanied by strange film sequences which were projected

onto the band along with "liquid (coloured oil slide) movies" -- the

product of experimental Lighting Designer Mike Leonard. Even at this

early juncture, while their contemporaries were busy playing at pop

stars, the Floyd placed little emphasis on themselves as performers,

preferring to give audiences an experience that relied on this

interaction of sound, light and atmosphere. Numbers like "Interstellar

Overdrive", which often lasted one hour, were based around one riff

or chord and, like rave music more than 20 years later, they sent

audiences on a magnificent sensory journey.

"Interstellar Overdrive", was, in fact, one of the titles performed

by the Floyd at their "Games For May" at London's Queen Elizabeth Hall

on May 12 1967, an event set up by their managers Andrew King and

Peter Jenner of Blackhill Enterprises, and promoted by classical pro-

moter Christopher Hunt. Not only did this mark the first appearance

at the hall of what was essentially a pop band, this "happening" also

marked the first appearance in Britain of a rudimentary quadraphonic

PA system, effected by additional speakers erected around the room and

an early version of an amazing device, which has now gone down in

Floyd folklore as the "Azimuth Coordinator". This elaborate name was

given to what was essentially a crude pan pot device made by Bernard

Speight, an Abbey Road technical engineer, using four large rheostats

which were converted from 270 degree rotation to 90 degree. Along with

the shift stick, these elements were housed in a large box and enabled

the panning of quadraphonic sound.

To augment the music, Waters rented a basement in Harrow Road to

record a number of effects tapes on a Ferrograph. These sounds

included backwards cymbals, distorted percussion, and fake birdsong,

and were played around the audience as the band performed. Waters

explained at the time: "The sounds travel around the hall in a sort of

circle, giving the audience an eerie effect of being absolutely

surrounded by this music." From this point onwards, it seemed, the

Floyd were destined to become pioneers in live sound.

WATKINS DOMINATED

Little in terms of purpose-designed PA technology existed before

1967, the only options open to the Floyd being Vox or Selmer columns

and 100 Watt amps. Therefore, when Charlie Watkins designed his first

WEM single column PA, the Floyd took it to their hearts, and it

remained with them for the next four years. The Floyd's system was

based around the WEM B and C cabinets. The B cabinet housed four

12-inch Goodmans 301 twin cone speakers, while the C cabinet had four

12-inch Goodmans Audiom 61s. Pinned in between the B and C cabinet

was an X32 horn in a narrow column. To drive the system, the Floyd

used WEM amplification, and Road Manager/Sound Engineer Peter Watts

mixed with four small five-channel WEM Audiomaster consoles whose

comparatively primitive functions included bass, treble, and middle

controls, presence and input sensitivity. This was the state of the

art back in the late '60s.

WEM founder and PA designer Charlie Watkins, who toured with the

Floyd during this period, says of their introduction to his system:

"A similar PA of mine had debuted at the Windsor Jazz & Blues Festival

in August 1967, and in the following month, Pink Floyd played through

one at the Roundhouse in Chalk Farm, and were immediately impressed,

because it was the only proper PA system capable of taking more than

100 Watts. They soon invested in a system, and as they earned more

money, they began to duplicate the amount of equipment until they

owned the most sophisticated PA in the country."

Armed with this state-of-the-art system, the Floyd -- now with

ex-Jokers Wild and Bullitt singer/guitarist David Gilmour who replaced

his drug-damaged pal Syd Barrett in March 1968 -- staged concerts,

which were promoted as "sonic experiences", and toured in 1969 with

their "Massed Gadgets Of Auximenes" extravaganza. A newspaper review

of the final date of this British tour described the performance as

including "electronic and stereophonic effects thrust around [the

Royal Albert Hall] from a battery of boxes and speakers. Edge of the

world sounds shiver; footsteps clump around the dome; voices whisper;

a train thunders; a jungle erupts."

Of an earlier concert at the Royal Festival Hall that April, Nick

Mason was quoted as saying: "The Azimuth Coordinator system might have

been improved if we had simplified it by having four speakers 'round

the hall instead of six. I am sure a lot of people couldn't

differentiate between each speaker. If we can develop this kind of

thing into an even bigger and better stage without getting too

technically involved, we will be going in the right direction." He

would not have too long to wait.

Meahwhile, Peter Watt's small crew (including Bobby Richardson,

Brian Scott, and Lighting Engineer Arthur Max) was joined by roadie

Seth Goldman, who began working for the band on their September-

October 1970 "Atom Heart Mother" tour of America and years later would

become their dedicated monitor engineer. Apart from the photograph on

the reverse side of 1969's "Ummagumma" album sleeve, the best evidence

of the touring equipment favoured by Pink floyd in the late '60s and

early '70s is the Adrian Maben film "Live at Pompeii", which was shot

in the summer of 1971 and shows the band's WEM system in all its

glory. But the end of that year witnessed a complete turnaround.

In 1971, Peter Watts became involved with audio pioneers Bill

Kelsey and the late Dave Martin. It was Martin who allegedly followed

a design by future Turbosound founder Tony Andrews and built the first

bass bin, which revolutionised PA technology. Martin, who had built

his first bass reflex cabinet at the age of 15, made a failed attempt

at designing a 4 by 15-inch bin with a detachable flare before

producing his definitive 800 Watt flanged 2 by 15-inch. The laws of

physics now began to govern live performance audio and instead of

literally adding more cabinets for extra reinforcement, bands were

able to "throw" their sound much further by using a combination of the

bass bin concept and Vitavox "voice of the theatre" horns.

In the May of that year, during a break from their "Atom Heart

Mother" tours and sessions for the "Meddle" album, Pink Floyd hired

the Wandsworth Granada [venue] to evaluate a new two-way passive Bill

Kelsey system, which initially incorporated seven-foot, 500-lb. RCA

"W" cabinets before switching to Martin's 2 by 15-inch bass bin.

Kelsey, who had already built PAs for King Crimson and ELP, recalls:

"What happened was indicative of the way the Floyd used to do business

in the days when they were more of a cult band. Peter Watts and Steve

O'Rourke (Floyd's manager) said they'd like to try a system so I went

down with all the gear, and then found there was another PA company

there and that it was to be an A/B test. Feeling a bit miffed that I

hadn't been told, I set up the gear as did the other company, and they

tried it out with the mixing console at the back of the hall.

"It seemed to be going all right, but Peter said, 'To be quite

frank, I'm disappointed... it's rubbish.' And Steve cut in, 'You

realise you've wasted my whole day, not to mention the cost of the

hall.' Peter continued to push up one fader to produce this horrid,

muffled sound, while the second fader produced a nice, clear sound.

I just wanted the ground to open up. Suddenly they both burst into

laughter and admitted they'd crossed the whole thing over." Despite

the elaborate wind-up, Kelsey's system was taken on board at the

beginning of the following year.

THE DARK SIDE OF THE MOON

Recorded over the course of seven months with the working title of

"Eclipse (A Piece For Assorted Lunatics)", "The Dark Side of the Moon"

catapulted Pink Floyd from their enigmatic cult status to the stadium

rock elite. Released in March 1973, it signified the first major

switch from their earlier psychedelic formula and set a new precedent

for record production which Floyd continued to build upon. As was the

case for many bands who moulded their material on the road for some

time before committing it to tape, the Floyd performed an embryonic

version of "Dark Side" both prior to and during their sessions at

Abbey Road throughout the whole of 1972.

The live rehearsals for this new concept piece were initially held

in Januyary 1972 at the now-defunct Rainbow Theatre in London's

Finsbury Park, and they were notable for both the first use of their

new sound and light systems, and the introduction of a new team

member. Mick Kluczynski had worked with a number of Scottish bands

since 1965, one of whom received an offer to record in London in 1971

as Cliff Bennett's backing band. Kluczynski accompanied them but the

whole deal soon fell to pieces. One of the band members, Chris

Adamson, survived by working as a Floyd roadie and arranged for

Kluczynski to also join their small team as part of the "Quad Squad".

"There was no formal crew, just four of us loosely employed to

handle all aspects of the sound and rigging," says Kluczynski. "My

first job was to empty the tour manager's garage, which was full of

all the old WEM PA columns and return them to Charlie Watkins, because

we had just taken delivery of the latest generation of PA. The 2 by

15-inch bins had a Vitavox horn on the top and a JBL 075 bullet super

tweeter -- I used to carry these things on my back up into balconies!

When we played the first Earls Court show, we used our maximum number

of Kelsey and Martin bins and horns. The bins were three high, with

13 at each side of the stage, and in the centre piece where there were

bins missing was a column of JBL horns. On top of those, we had a row

of double Vitavox horns, on the back of which were throats that we had

made up, which took two ElectroVoice 1829 drivers in the same throat.

ElectroVoice claimed it wouldn't work, but we got up to four in one

throat. One quad section would drive two horns in one phase direction,

and another quad section would drive another two in the opposite phase

direction. But EV wouldn't believe it until they saw 15,000 people

walk out of Earls Court at the end of the night dazed and speechless."

In an A/B text during rehearsals, the band's existing WEM amplifiers

came second place to the new American Phase Linear models, discovered

by Kelsey, and so yet another injection of quality was given to their

PA. It was common for Pink Floyd to modify off-the-shelf equipment for

their own purposes, thereby creating unique products. Along with Crown

and BGW, Phase Linear became one of the few brands of amplification

taken seriously by the top touring bands of the early '70s. Whilst

the Phase Linear 400 and 700 models were taken on board by the Floyd,

because of their superior sound quality, in their regular domestic

format they were unfit for the rigours of the road due to their slight

physical construction and the weight of the transformers on their

chassis. To compensate for this, the band's technicians designed a

new metal chassis into which the amp would fit, while the mains

transformer was removed from the amp and supported horizontally on the

outside of the chassis.

Acclaimed by critics as "rock's first conceptual masterpiece",

"The Dark Side of the Moon" was premiered as "Eclipse" over the four

nights of February 17-20 at the Rainbow, by which time the band had

been touring in the UK with their new system for a month. The standard

show at the time consisted of two sets: the first featured earlier

numbers such as "Set The controls For The Heart Of The Sun", "Careful

With That Axe Eugene", and "Echoes"; the second consisted of what was

to later be known as "The Dark Side of the Moon" (then without the

"Eclipse" finale which was yet to be written). "One Of These Days"

was reserved as a breathtaking encore. These previews of the

forthcoming album amounted to something of a bootleggers' paradise.

A poor live recording of "Dark Side" was available through the German

black market for around a year prior to the studio album's release,

and although the band were horrified, it could be said that this

created even more interest in the real thing.

Kluczynski recalls that his first show as a crew member, the

opening night of this tour at the Brighton Dome, ended in disaster.

He says, "In those days, we didn't understand how to separate power

sufficiently between sound and lights. That was the only show that

we had to cancel and reorganise, because we were all sharing the

same power source. The Leslies on stage sounded like a cage full of

monkeys, because they were sharing a common earth. It was the very

first show that any band had done with a lighting rig that was powerful

enough to make a difference. So we had this wonderful situation where

the fans were actually inside the auditorium, and we had Bill Kelsey

and Dave Martin at either side of the stage screaming at each other in

front of the crowd, having an argument."

BOARD DECISION

Another vital piece of kit added to the Floyd inventory at this

time was a 24-channel mixing console manufactured by Ivor Taylor and

Andy Bereza of Allen & Heath, a new company which took its name from

a defunct toolmaking firm. Bereza, the man resonsible for inventing

what became the Portastudio, originally built mixers at home in the

late 1960s under the trading name of AB Audio and was responsible for

the board used in the live soundtrack recording of the cult movie "A

Clockwork Orange", as well as mixers for bands including The Bee Gees.

The Allen & Heath business grew steadily in its first year with its

small six-channel boards, many of which were used in cathedrals,

churches, and small theatres, as part of installed public address

systems. Then an opportunity arose for the company to build a

quadraphonic desk for The Who, news of which filtered into the Floyd

camp, and an order was placed for a custom quad board in advance of

the first "Dark Side" rehearsals.

Future Floyd Production Director Robbie Williams, who joined the

crew in January 1973 just as Seth Goldman took a long break to work

with ELP, Three Dog Night, and T. Rex, remembers his first sighting of

the desk. "This board was actually the reason for my involvement with

the band. I was a frriend of Peter Watts and had always been

interested in the audio business. One day in November 1972, I went

'round to his flat to see him in the process of taking this console to

bits and rebuild it in time for some shows with the Roland Petit

Ballet in France the following January. To me at the time, it was the

most magnificent piece of electronics, about the size of my coffee

table. Peter had bought the very first Penny & Giles quad panners on

the market, and I spent the next month helping him rebuild this thing."

The quad function on this desk was given the name "Sound-In-The-

Round", and unlike conventional quad, the speakers were positioned

front, back, left, and right in a diamond, with the front channel

situated behind the band. On the desk, any channel could be routed

into the quad section, which was operated via the pair of joysticks on

the right of the board. The quad function, however, came into use as

an enhancement for sound effects or occasional solos.

Williams, who in the late '60s earned his roadie stripes through

working for the seminal lighting company Krishna Lights, says: "After

helping Peter get the desk match fit, I asked him, 'Does this mean I'm

part of the crew?' To which he replied, 'Well, I guess you'd better

come out to Paris and give us a hand, just in case anything happens to

the desk.' And it went from there. When I joined, the crew consisted

of Peter, Mick, Chris Adamson, Graeme Fleming, Robin Murray, and

Arthur Max. I was very much the under-assistant truck packer for the

PA department, and through the '70s as Pink Floyd's fame grew, so did

my responsibilities."

Kluczynski says of the Allen & Heath mixer: "It did tend to be a

little unreliable, but it kept going, even though Seth Goldman and I

would each have to take a corner and jolt it into life every day!

We'd even driven it with truck batteries at the Rainbow during the

power strikes. We would be in Newcastle one night and have to nip

back to London to get it fixed in the middle of the night, and then

travel back up to Sheffield or somewhere for the next gig. The quad

panner for the second Allen & Heath desk we used [built in the bottom

of a lift shaft in Hornsey in 1973] was actually made from cut

Elastoplast cans and there was a read-out panel in the middle, which

was a circle with quadrants in it. As you panned, you could see the

quadrant you were in which pulsed from green to red. When you removed

this panel and looked underneath it, you saw that these Elastoplast

cans had been cut to make a spiral in which the LEDs were inserted to

give you the pulse reading."

This was not the only amazing do-it-yourself story... "Around late

1974, we bought a Sony hi-fi crossover, but before that we were running

the PA full-range," says Kluczynski. "The only protection Bill Kelsey

put in for the high end was through having crossovers built into Old

Holborn tins and placed inside the cabinets. In the more sophisticated

version, there was a light bulb in line. If you were to overdrive the

cabinet, the light bulb went white hot, but the horns didn't blow up!"

PARSONS'S MIX

Towards the end of the recording sessions for "Dark Side" in January

1973, Pink Floyd relocated to Paris to work on music to accompany the

Roland Petit Ballet. Added to the growing crew on this occasion were

Robbie Willams and Alan Parsons, the "Dark Side" Studio Engineer who

had been lured away from Abbey Road to replace Chris Mickie behind the

front-of-house console. Parsons's appointment began an unusual trend

for Floyd to hire the services of whichever studio engineer had worked

on their latest album (although this ploy was not always successful),

and like many of his successors, he was a total novice in the concert

environment.

Parsons, whose only other work as a live sound engineer was for

Cockney Rebel at Crystal Palace, says: "I was due to go on a skiing

holiday when I was asked over to the Palais des Sport in Paris to

learn the ropes at some shows they were doing with the ballet, and I

remember that a lot of the movements were based around "One Of These

Days". They should have done more of those performances, because the

whole concept of a rock band with lights and special effets, and a

brilliantly choreographed dance routine was just stunning. I was

literally dropped in at the deep end when they said, 'Come and see one

of the shows, and then you can take over as our engineer.' So after

watching Chris Mickie behind the desk in Paris, I took over and stayed

with them on the road for about a year or so, which included two

American tours."

When mixing the Floyd, Parsons says that his obvious main concern

was avoiding feedback -- a task made difficult by the speaker

positioning and the close proximity of the front stack to the band.

"You'd be standing on stage and almost have the horns pointing straight

at you," comments Parsons. "But the performance of that rig was so

pure; there was no pink noise, no graphic EQ to tailor the sound, it

was literally down to how you drove the bottom, mid, and top."

As well as recalling the excellent quality of this PA's sound,

Parsons casts his mind back to an American tour date in Detroit when

many of the system's components were wiped out by pyrotechnics. "By

mistake, the flashpots at the front of the stage had been filled twice

with explosives. The result was a double-strength explosion, which

ended up injuring several people in the front row of the audience.

Unfortunately for us, it also destroyed about 60% of the horns and

bins, so we had to struggle on for the rest of the show with less than

half our PA rig. Of course, we had a gig the next night and finding

replacement gear was a major headache."

The aspect of Floyd's sound that Kluczynski remembers most was

David Gilmour's guitar sound. "Gilmour was always loud, especially at

Earls Court where, during the solo in 'Money', his four 4 by 12-inch

cabinets were screaming away at such a level that we couldn't physically

put him through the PA. Most of the time I'd mix the solos, because

Alan was a bit shy of pushing up the faders compared to me, so I'd

nudge his arm a bit!"

In complete contrast to today's standards, Pink Floyd employed just

two outboard devices for use at front of house on the "Dark Side"

tours, and both of them were Echoplexes for the repeat vocals on "Us

And Them". Williams says: "The band members would treat their own

sounds and produce effects on stage themselves, which is essentially

what happened in the studio. So the sound heard through the PA was

generally what came from Gilmour's amps, for example. Each of them

had a stack of those dreadful Binson Echorecs and Echoplexes [based on

circuitry designed for a GPO telephone switching device]. Rick Wright

had a little keyboard mixer that had a couple of effects sends on it,

which used to go into various Binsons, and there was a feed going from

that to front of house. For the early "Dark Side" concerts, he also

had personal access to the "Sound-In-The-Round" via a joystick on his

mixer."

As for microphones, for years Roger Waters insisted on their

trademark rectangular Sennheiser vocal mics (gold one side, black the

other). Parsons says: "The choice was certainly individual, and they

didn't sound bad. Generally, we used dynamic mics. There were a lot

of SM58s floating around for backing vocals, as part of a Shure setup.

At nearly every gig, I would have to re-position the mics a foot away

from the guitar cabinets, because the crew would always ram them right

up against the grilles, which in my mind was ridiculous. I was always

frustrated that whenever I got a really good sound on one gig, the

crew would break down all the gear and load out at the end of the

night, and all my settings would be lost. So I literally had to start

from scratch every night, checking the mics through the desk. The

crew would say, 'Oh, we've put the guitar on a channel over here,

because that channel wasn't working,' so all of my previous checks

were rendereed useless. Drums were always critical, so I had this

idea of buying a little six-channel Allen & Heath mini mixer which I

took home with me every night in a briefcase!"

Crucial to the "Dark Side Of The Moon" concept, both on record and

live, were the sound effects which included various human voices, a

heartbeat, explosions, the "Money" cash register, and, for "Time", the

(alarming) clocks. Parsons himself recorded the clocks for the album

on an EMI portable quarter-inch tape machine and later fed through the

live quad mix to the astonishment of audiences around the globe. He

says: "We went back to the album multitrack tape to copy those clocks

and other effects for the live shows, and played them through the quad

system on a TEAC four-track deck. For some reason, the board was

miswired inside and instead of playing them through the PA as tracks

1,2,3,4, the board sent them out as 2,4,1,3. I was never able to

remember exactly which order it was, so I always carried a test tape

with me to ensure that the channels were all coming out in the right

place. I had Mick Kluczynski firing up the tape machine and would

give him a nod to hit the play button in the right places. We had a

tape for 'One Of These Days', which included the big, thumping drum

sound and Nick Mason's distorted vocal effect which said, 'One of

these days I'm going to cut you into little pieces." Mick had been

touring with the band almost as long as they had been performing it,

but it seemed he could never fire up the tape in the right place

without a cue from me."

Kluczynski confirms that prior to the four-track TEAC machine, he

had been using a four-track Sony for sound effects. The band later

progressed to eight-track Brennells when, Kluczynski says, "Allen &

Heath ceased to exist for a while as we knew it, and the key personnel

had moved to Brennell, including Nigel Taylor [brother of Allen &

Heath troubleshooter Ivor], who we later poached for our crew."

THE MONITORING VIRUS

The 1972 and '73 "Dark Side" tours were notable for the Floyd's

first use of stage monitoring, although it remained minimal until

their "Animals" tour four years later. Never a fan of monitors,

Kluczynski says that once the first wedges appeared, they began to

spread like a virus and front-of-house engineers quickly realised a

they had a struggle for control on their hands. Before the advent

of monitoring, Kluczynski maintains, the band were able to hear each

other clearly by keeping a sensible level on stage. "During a show,

you could walk around the back of the Floyd stage and have a normal

conversation, because overall they never played too loud, apart from

Dave. The band literally heard themselves off the backline and what

was coming back at them from the PA. They were very much into the

environmental sound of the house and the pure feel of their music.

Because they had no monitoring, there was never the battle between the

instrument and the wedge. Subsequently to hear themselves, they kept

the general level down, which was really good and incredibly well-

disciplined. There was never any ego bullshit in that department.

"The first monitor we brought in was when Dick Parry came on the

tour as sax player. Dick had to have a monitor, because his

instrument was so loud to him that he couldn't hear the band without

one. The next addition of wedges came when our three female backing

vocalists walked on stage and said, 'We'll come back when you've

finished setting up.' We said, 'We have finished.' They said, 'Where

are the monitors then?' 'The what?!' So we got a couple of Tannoys

and stuck them in boxes for them."

Williams, who loathes the very concept of monitoring with a

vengeance, comments: "Dave, who stood next to the girls, said, 'Oh, I'll have one.

Sound On Stage number 6, April 1997

"Welcome to the Machine - the story of Pink Floyd's live sound: part 2"

In the wake of their huge success with the "Dark Side Of

The Moon" album and tours, Pink Floyd graduated to stadium

status and helped to shape the future of top level touring

sound with the formation of their own PA rental company.

In the second installment of this four-part series, MARK

CUNNINGHAM chronicles the band's "Wish You Were Here" and

"Animals" period of the mid-70s.

After two American tours which had seen the debut of their new

three-way active PA systems, Pink Floyd returned to Blighty {that

is, England} to make their only UK concert appearance of the year,

at the Knebworth Festival on Saturday 5 July 1975. This performance

witnessed the live premiere of the forthcoming album, "Wish You Were

Here", nine weeks before its release, and it came exactly seven days

after the Floyd's last North American date in Toronto, the end of

which was notable for a huge unplanned pyrotechnics explosion that

resulted in the shattering of several nearby residents' windows!

Mick Kluczynski's foreign duties at the time included clearance

of equipment into a country, arranging trucks, and organising load-

ins. At the end of a tour, after the band and crew returned home,

he stayed to supervise the trucking of all the equipment and then

do the bookwork. With Knebworth so close, it was decided that

Robbie Williams and Graeme Fleming would prepare for Knebworth in

Kluczynski's absence during the early part of the week.

Kluczynski recalls: "The gear arrived back in the UK on the

Wednesday, and it got to Knebworth on the Friday morning ready for

rigging. We had ordered some JBL long-throw horns, the old seven-

foot-long fibreglass festival horns, but didn't get delivery of them

until the Friday night. So literally on Saturday morning, Robbie and

I were building them into the rig. We had the Floyd set up totally

independent of the support bands [which included Captain Beefheart

and Linda Lewis], which was the normal approach for us, although we

would normally run the show for them. However, because the Floyd crew

had been on tour, we ended up engineering just our own section of the

show, and I brought in Trevor Jordan, Bryan Grant, and Perry Cooney

(ex-IES) to look after front of house for the support bands and do

the changeovers on stage, so Robbie was fresh for the Floyd."

Seth Goldman had been mixing the monitors for the band on their

American dates but, as Taylor recalls, the decision was made that it

was not financially viable to finance his return trip purely for the

Knebworth show. "I think Nick Mason was the one who said, 'We're not

paying for him to fly back for just this gig, we'll get someone else.'

And we ended up using a Scottish guy from IES called Arnie Toshner.

I had only been around for about a year, and I remember thinking how

strange it was that a band this big would quibble about such an

expense!"

While the first half of the Knebworth set was dedicated to the

forthcoming album material, complete with specially commissioned

Gerald Scarfe animation projections, the second set was Floyd's

last ever complete live re-creation of "The Dark Side Of The Moon"

to feature Roger Waters, and was followed by "Echoes" and a dazzling

fireworks display. Backed yet again by sax player Dick Parry,

vocalists Venetta Fields and Carlena Williams, and special guest Roy

Harper, who delivered his "Have A Cigar" vocal, Floyd's performance

was little short of perfect. Or at least that's how it seemed to most

of the fans. Behind the scenes, however, the crew were suffering a

technical nightmare.

For previous outdoor festivals, Floyd had used the Mole Richardson

generator trucks that were common in the film industry, but Knebworth

was the first instance where the band's crew had to book generators

themselves. "None of the other acts prior to Floyd used keyboards,

so voltage fluctuation didn't bother them," says Kluczynski. "But

the generators that had been booked weren't stabilised, and to silence

them, they were situated off stage with straw bales all around them.

When the Floyd went on, the keyboards were all out of tune and sounded

terrible, and then the straw caught fire! If we'd have known of the

hazards, we probably would have run the keyboards from batteries, and

it would have been just as effective. So Knebworth was Robbie's

baptism of fire as a production manager, but you learn!"

This was not the first disaster to befall the floyd that summer

evening. Unlike recent shows where a model aeroplane had featured in

the band's production, the plan was to book two real Spitfires to do

a flypast as the introduction to the performance. Frustratingly, the

planes arrived early as they needed to return to base before dark, and

a rather long and embarrassing pause followed. The band were even

more red-faced a few weeks earlier during their American tour when a

new item in their set design did not prove quite as user-friendly as

they'd hoped. Seth Goldman says: "They were always into great ideas

and one of them was to cover the entire stage in a helium-filled

pyramid, which served both as protection in the event of rain and also

as a visual prop when it was hoisted several hundred feet above the

stage. Unfortunately, it died on the first open-air gig in Fulton

County Stadium, Atlanta [June 7 1975]."

As the pyramid rose up above the walls of the stadium, the wind

took hold and it was blown into the car park whereupon a group of

frenzied fans ripped it into pieces. "That was the end of our roof

for that tour!" says Taylor of this Spinal Tap-like episode. "When we

played in Milwaukee County Stadium, it poured with rain and the band

had to do most of the second set with a tarpaulin just above their

heads, which was supported by a few of us standing around them on the

stage with eight-foot scaffold poles. It was fucking hilarious but

very dangerous, with two inches of water at our feet. But 'Echoes'

was fantastic, because the crowd were all soaked, but suddenly they

could see the band properly, and because the stage was so wet, the

dry ice looked better than ever. It was just a marvellous finale!"

BRIT ROW

By 1975, Pink Floyd had accumulated a substantial arsenal of sound,

lighting, projection, and staging equipment, which was now overseen

by a formidable road crew. When the band returned that June from

their second American tour of the year, with no imminent touring

plans, they made the decision to keep their crew employed and maximise

their investment in equipment by hiring it to outside parties.

For years, the Floyd's road crew led a nomadic existence, storing

equipment in temporary locations, such as the fourth floor of tour

management legend Rikki Farr's apartment block or in garages near

Portobello Road. But now a permanent storage home had been found for

the Floyd's wares in the form of a converted chapel in Britannia Row,

a difficult to negotiate side street close to Roger Waters's home in

Islington, North London. Britannia Row Productions was born, making

its official debut at Knebworth.

"Brit Row was really started to give a reason to not fire the

crew," explains Williams. "So they gave Mick and I the opportunity

to run Britannia Row Audio, and Graeme Fleming the responsibility of

Britannia Row Lighting."

"Robbie and I thought long and hard about it," adds Kluczynski.

"Up until 1975, we were touring for something like nine months a year,

and then it changed to six months every two years. We were on wages

all that time, so for 18 months we would be doing nothing unless Dave

Gilmour asked us to provide a system for a free Hyde Park gig he was

doing, and it was becoming difficult to justify our existence."

In the early days, Brit Row suffered from the kind of naive

business logic that the Beatles displayed with their Apple venture.

As a fledgling rental facility, the organisation faced two major

problems. Because Floyd rarely toured with a support band in the

'70s, Williams's and Kluczynski's lives had become incredibly insular,

therefore forming relationships with management companies in order to

pitch Brit Row business required considerable effort. Also, Brit Row

was only allowed to operate with the Floyd's existing equipment; any

further investment in stock had to be paid for out of profit. While

their speakers and bass bins could equip as many as five average

bands, with just one front-of-house desk the company could only

service one tour at a time.

"Until we could get far enough ahead to buy that second mixer, we

were stuffed," Kluczynski says. "We had minimal foldback, so for us

to actually start the company properly, we needed two monitor systems

and at least another front-of-house desk. We did okay within our means

though. Then the band went back on the road for half of '77, which

effectively closed us down.

"Our maximum continuous touring period was 21 days, during which

Steve O'Rourke could book as many shows as he wanted. So we would

often tour America in four 21 day periods with two week breaks in

between. To maintain some kind of presence throughout the world while

we were away in '77, we split the main PA in two, one half of which

was joined by another mixer and left in London for Perry Cooney to run

for us. The other half went to Long Island with a view to attracting

American clients, and as I had an American girlfriend, I went with it.

It was bloody hard work! In the end, I was sub-contracting the gear

to Tasco and other service companies, and it all started to get very

messy. That's when I bailed out and went freelance." Kluczynski now

runs his own successful company, MJK Productions, working on a wide

range of tours and events including The Brit Awards.

During 1979, New Zealander Bryan Grant, formerly a sound technician

with rental company IES and an advance man on Floyd's '75 tour, joined

Britannia Row to rationalise the business and improve communications

between departments. Kluczynski was now out of the picture, having

given up hope of turning Britannia Row Inc. into a successful operation.

Grant settled into devising and selling recording and touring packages

to prospective clients. "We carried on like that until 1984 when Robbie

Williams and I bought the equipment from the Floyd and set up Brit Row

as an independent organization. It was then that we concentrated on

audio," says Grant of the company which has since reactivated its

American base and become one of the most successful audio rental

outfits in the world.

ANIMALS IN THE FLESH

During the next year off the road, David Gilmour guested on various

projects; by artists including Cambridge pals Quiver, the band which

featured future Floyd sidemen Willie Wilson and Tim Renwick, and backed

the Sutherland Brothers on their hit "Arms of Mary". As executive

producer, he also assisted with demo sessions by a young Kent songstress

named Catherine Bush, after which Pink Floyd reconvened in April 1976

in their own newly-built recording studios at Britannia Row to work on

their next album, "Animals".

On the day of its release, January 23 1977, the band played the

first date of its "In The Flesh" European tour in Germany at Dortmund's

Westfalenhalle, and later embarked on American dates which climaxed on

July 6 at Montreal's semi-built Olympic Stadium. Despite the fame and

fortune earned by the Floyd over the previous four years, this new

production showed that creatively the band were showing no signs of

complacency. Their trademark visual prop, the giant porker, made its

debut on this tour as one of several inflatables, and new film footage

had been shot to accompany the "Animals" material.

Kluczynski, who on this tour handed his effects tapes responsibilities

to studio engineer Brian Humphries and took on the role of production

manager, comments: "This was the first tour we did where we had to use

click tracks and the music synchronised to the film, hence Roger Waters

needed to wear headphones."

The "In The Flesh" tour marked yet another transition in Floyd's

statistic-busting live career. In complete contrast to what was

acceptable to the new Punk philosophies [remember Johnny Rotten's

"I Hate Pink Floyd" T-shirt?], stadiums and large arenas were now the

only places which could physically accommodate the Floyd's multimedia

presentations, and in many cities, they were at least doubling the size

of their audiences. Similarly, this governed a notable increase in the

size of Floyd's PA. Active crossovers came into the picture on the

"Wish You Were Here" tour as the band introduced a new three-way active

PA with Martin bins. For the 1977 tour, Bill Kelsey designed a four-way

active system, which comprised of Kelsey bins, 2 x 15-inch blue fibreglass

front-loaded mid cabinets, Altec horns, and JBL 075s. Augmented by

additional horns and bins depending on the sizes of venues, this formed

the core of the Britannia Row PA system. Karl Dallas praised the sound

in "Melody Maker", writing in his review of Floyd's January show at

Frankfurt's 12,000 capacity Festhalle: "It all adds up to the clearest

sound I have ever heard in a hall this size."

On the eve of the North American leg of the tour, Kluczynski and

Graeme Fleming made an advance check on the first outdoor venue,

Atlanta Stdium, to gauge the extent of the PA equipment and sound

power required. Kluczynski: "I walked down onto the field and started

looking upwards, and up, and up... I suddenly went into a blind panic

and couldn't wait to get on the phone to Robbie in London to tell him

to double what we'd ordered!"

The actual configuration of the PA and the mix passing through it

signified a change of direction -- one which borrowed much from the

techniques of The Grateful Dead and their Meyer Sound-designed system.

Rather than rely on conventional backline amplification, the Dead

placed PA columns along the back of the stage and gave a final mixed

feed directly to the front-of-house engineer. Each column of the PA

contained one instrument, and then each group of columns would be

repeated along the PA stacks in a huge "wall of sound".

"We adapted that idea, but instead of having a wall of columns

along the back of the stage, we split our system left and right and

made that the principle for our PA," recalls Kluczynski. "This meant

we were up to 36 foot high to gain the projection required, whereas

until then we had been stacking horizontally simply because of the

nature of the venues. Our quad development paralleled these changes.

We previously had four points, but we now eliminated the back point --

because it was irrelevant -- after realizing that the sum total of the

three quad stations should equal the whole PA, so there was an equality

in volume throughout." The equipment and technical rider for the tour

recommended that each of the three quad towers "should be two metres

high by four metres long by two metres deep, with three meters

overhead clearance".

The Phase Linear 400 and 700 amps used by the Floyd since the early

'70s were re-racked at the end of 1974 by Bill Kelsey and Peter Watts,

who had replaced the Phase Linear front panels with new engraved signs

which read "Pink Floyd Power Amp". In preparation for the "In The

Flesh" tour, the band purchased the new and more powerful Phase Linear

Dual 500s, and Nigel Taylor supervised their custom racking inside a

Brit Row-built 19-inch cube-shaped chassis. Each chassis, which

housed two amplifiers, was designed to enable simple disconnection of

wiring for servicing on a workbench.

A major change was happening in the console department in 1977.

While Brian Humphries mixed at front of house with the Floyd's new

custom-designed double Midas console (see box "Mirrored Midas"), Seth

Goldman engineered the monitors using a standard Midas 24:12 console,

which he also remembers using in America with a variety of bands

throughout 1979 as part of Britannia Row Inc's hire stock. Use of

outboard equipment for live concerts was beginning to grow, and the

front-of-house racks now included Klark Teknik DN27 graphic equalisers.

Robbie Williams also recalls that one of the first truly influential

items of outboard equipment made its debut with Floyd on the "In The

Flesh" tour: the Eventide Harmonizer. "We got hold of it because one

of Eventide's guys was a die-hard Floyd fan and he had made this huge

piece of equipment. Gradually, noise gates and more and more outboard

began to appear, until it looked like we were carrying a recording

studio on the road."

ALIENATION

Although a real step forward technically, "In The Flesh" proved to

be the most unhappy tour of the band's career. Now distanced from

each other as individuals, the magic had long since evaporated;

matters finally came to a head on the last date of the American leg.

In interviews while on the road, Waters had reported his frustration

at the "meaningless ritual" of live performance, where his intensely

personal songs were treated with a lack of respect by "whistling,

shouting, and screaming" audiences. In Montreal on July 6, he took

it out on an innocent fan in the front row by spitting in his face.

"On that 1997 tour, Roger was definitely becoming unpredictable and

was changing a lot as a person," says Robbie Williams. "The last gig

was pretty awful, because he was shouting abuse at the audience when

they wouldn't shut up during the quiet numbers."

Some years after the fateful tour, Waters commented: "We played

to enormous numbers of people, most of whom could not see or hear

anything. A lot of people were there just because it was the thing

to do. They were having their own little shows all over the place,

letting off fireworks, beating each other up and things like that.

As the tour went on, I felt more and more alienated from the people

we were supposed to be entertaining." Stadium rock had become such

an isolating experience that he imagined building a wall between the

band and its audience. Now, there was an idea.

Next month: "The Wall"

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Sidebars:

PINK IRONY

Little more than two years before Pink Floyd embarked on their

enormous "In The Flesh" tour of the USA, Rick Wright said: "I don't

agree with these huge shows in front of tens of thousands of people.

Wembley Empire Pool is the biggest place you can play before you

lose the effect."

SLY PORKER

The legendary inflatable Floyd pig was conceived by Roger Waters

and originally designed by ERG of Amsterdam in December 1976 for the

photo session at Battersea Power Station which spawned the "Animals"

album cover. The original porker went missing when it broke free from

its ties during the shoot and flew across the Home Counties, much to

the disbelief of aircraft pilots!

A replacement was made in time for the launch of the "In The Flesh"

tour in Dortmund in January 1977, where it emerged from over the PA

stacks through a cloud of black smoke during, appropriately, "Pigs

(Three Different Ones)". It has since become a staple prop for every

Floyd tour. When Roger Waters left the band in the mid-1980s, part of

the settlement stipulated that he would be paid $800 every time his

ex-colleagues performed live with the pig (a sow). In a bid to avoid

paying this royalty (and at the same time possibly deliver a thinly-

veiled sarcastic message), Gilmour and co. added testicles to the pig

and claimed it was a different beast altogether. That's balls for you.

SNOWY WHITE

Added to the Floyd's lineup for the 1977 "In The Flesh" tour was

guitarist Snowy White, who had impressed Steve O'Rourke with his live

work for Steve Harley & Cockney Rebel and Al Stewart. Those who

purchased the eight-track cartridge version of "Animals" will be

familiar with White's brief guitar solo, which linked the two verses

of a rare, composite version of "Pigs On The Wing".

He was hired yet again in 1980 to support Gilmour on the "Wall"

shows as one of the "surrogate band"; his role was made all the more

difficult by his commitments with Thin Lizzy. He says: "It was a

crazy period where I was learning two bands' material, which were

totally different to each other, all at once. Floyd were rehearsing

at Los Angeles Sports Arena, and every morning in my apartment, I

would spend a couple of hours going through Lizzy songs, then polish

up on the Floyd stuff before going to rehearse. It was a busy time."

White would later perform at Roger Waters's "Wall" extravaganza in

Berlin in 1990.

MIRRORED MIDAS

In November 1976, Midas, whose key players were Chas Brooke (of BSS

fame), Geoff Beyers, and Dave Kilminster, began designing a new Pink

Floyd custom console, which Kluczynski describes as being a radical

step forward in front-of-house control. This console as a whole,

which was completed just in time for its debut on the "In The Flesh"

tour, was formed from two separate mirror imaged desks, each side

containing twenty channels but operating as one large forty-channel

board. In total, there were eight stereo sub-groups and eight effects

busses, and each input had three controls, which could be assigned to

any of the effect busses via the buss transfer electronics.

The left-hand desk had inputs 1-20, effects returns 1-4, and aux

masters 1-4, while the right-hand board had inputs 21-40, effects

returns 5-8, and aux masters 5-8. All channels had routing switches

to sub-groups (S1-8) and six quad sub-groups (Q1-6). EQ was three-

band with various switchable frequencies. In between the two boards

sat a new Midas quad board with joystick panners for each of the quad

sub-groups. This separate board had four four-channel returns for

effects, each of which featured trim levels and a diamond-shaped mute

switching layout.

Robbie Williams poetically describes this desk package as being

"the dogs bits at the time". He adds: "It wasn't the traditional

Midas grey either, it was finished in a lovely aubergine colour and

really was a splendid piece of kit. By the time we ordered it, we

were already operating Brit Row as a rental company, so we had our

eyes on the future." Even more impressive was its multi-coloured

screen-printed graphics, which were applied with ultraviolet inks.

A UV light unit, fitted over the meter bridge, flooded the work

surface, enabling the desk to shine brilliantly (and allow foolproof

operation by the engineers) in the darkness of an auditorium. "It

looked absolutely stunning," says Chas Brooke. "No one had done

that before, and probably no one since, because it cost a fortune.

Manufacturing such an elaborate console meant, of course, that it

was impossible to make any money out of the exercise, but it was

definitely worth the effort."

The quality of this unusual console package owed much to its

state-of-the-art op-amp, the Philips TDA 1034, which was the fore-

runner of today's standard 5532 and 5534 op-amps. Says Brooke:

"This was a very expensive, ground-breaking, military specification

linear op-amp in a metal case (unlike today's more common plastic-

cased variety), and we decided that Pink Floyd deserved it for this

console. As such, this was one of the very first consoles to use it."

The console is now owned by a small rental company in France.

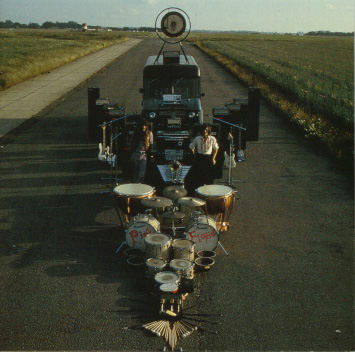

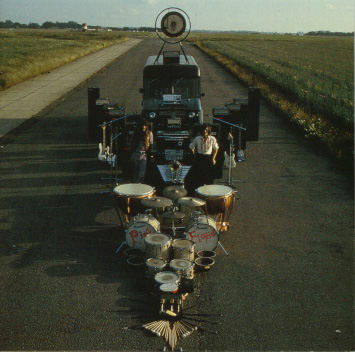

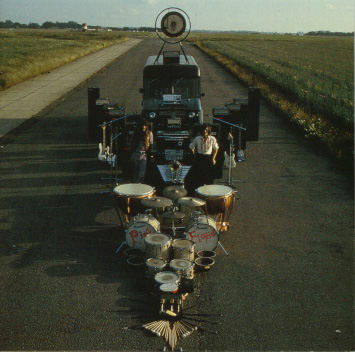

Photo caption:

"Pink Floyd's 1975 classic "Shine On You Crazy Diamond" was performed

live for the first time in the UK on November 4 1974 at the Usher Hall

in Edinburgh -- the first date of their autumn/winter British tour.

Before the doors opened, the road crew posed for this rare photograph

which also shows the band's second generation Allen & Heath desk,

lighting console, the TEAC four-track tape machine for sound effects,

and the PA stacks with the front quad speakers at the right-hand side

of the circular screen. {List of people pictured: Paul Devine (lights),

Graeme Fleming (Lighting Director), Peter Revell (projectionist),

Coon (intercoms), Bernie Caulder (quad and drum technician), Robbie

Williams, Paul Murray (projectionist), George Merryman (technician),

Mick Kluczynski, Nick Rochford (truck driver), Mick Marshall (lights),

Phil Taylor. "...Rick Wright is seen tinkering on his grand piano."}

Sound On Stage number 7, May 1997

"Welcome to the Machine - the story of Pink Floyd's live sound: part 3"

MARK CUNNINGHAM continues his comprehensive study of Pink

Floyd's classic tours and goes behind the scenes of the

most outstanding live production of the 1980s: "The Wall".

Although their eagerly-awaited follow-up to "Animals" began life

at Britannia Row Studios, Pink Floyd were soon forced to spend most

of 1979 overseas as tax exiles and completed the recording of their

new album in the South of France, Los Angeles, and New York. In the

mind of Waters, its author, "The Wall", like The Who's "Tommy", was

always going to be more than just a double album; it also generated

a controversial Alan Parker-directed movie and one of the most

ambitiously theatrical rock concert productions of the modern era.

Harvey Goldsmith had been involved in promoting almost every

major Floyd tour of the previous 10 years, but nothing could prepare

him for the sheer expanse of "The Wall", a project originally born

of Waters's reaction against stadium rock. He says: "Roger Waters

took me out for dinner one night and said, 'I have got this idea,'

and he started to tell me about this story. He said, 'I want to

build a wall between the band and the audience, and as the show

progresses, The Wall will build up and up and up...' The bricks

were all cardboard, of course, but I told him that on the last show

there should be a concrete wall, so we could do it for real! We

talked it through and he pretty well had the whole show in his mind.

Then we started liaising with Fisher Park [set design specialists

Mark Fisher and Jonathan Park] to create that event which marked a

big turning point in the history of live shows."

Throughout the making of the album, plans were being drawn up

for the forthcoming production, based on Waters's bizarre concepts.

As well as a number of massive inflatable puppets based on Gerald

Scarfe's distinctive "Wall" cartoon sketches of the schoolteacher,

the mother, and wife, the central "prop" was the "Wall" itself:

420 white, fireproof cardboard bricks built 31 foot high and 160

foot wide. It was slowly constructed in front of the band during

the first 45 minutes of the show by the six-man Britro Brick

Company (!), until Roger Waters slotted the final brick into place

at the end of "Goodbye Cruel World" to signify the intemission.

The show climaxed with the collapse of the wall against a volley

of explosive sound effects and smoke. An encore would have been

a trivial irrelevance.

Says Robbie Williams: "I always knew 'The Wall' was a killer

album, and that we'd go out and tour it, although most of us

assumed it would just involve a slightly bigger PA system and a

few lasers. I don't think anybody had any conception of what was

going on in Roger's mind, and when we first heard that he wanted

to build a massive wall across the stadium with the band performing

behind it, we all said, 'You've got to be f**king mad!' We thought

the audience would storm the stage and that the poor guys at front

of house were going to get killed."

Unable to enter the UK for tax reasons until April 5 1980,

Pink Floyd held the live premiere of "The Wall" at Los Angeles

Sports Arena on February 7 1980, then move to Nassau Coliseum

in New York for five shows, before finally playing six London

dates at Earls Court on August 4-9.

AT FOH

In deciding upon the most suitable front-of-house engineer,

the bass player had only one person in mind, and "The Wall"'s

co-producer and engineer, James Guthrie, was approached by Waters

several times on the subject. Guthrie, who began his studio

career at Mayfair Studios in 1973, says: "I was quite opposed to

the idea initially and told him, 'Look Roger, this is a whole

different area of expertise. You should get someone more suited

to the job, because I have only ever worked in studios.' As time

went on, the project became more and more complex. Gerald Scarfe

had already begun working on the animation which was used for both

the film and live shows, as well as graphics. While we were in

France, Roger cornered me yet again and quite abruptly said, 'You

are the only person qualified to mix the live show, so you have to

do it.' He was also enticing me by saying that we could get any

piece of equipment we wanted, and being as I'd always liked a

challenge, the prospect became more exciting by the day. I finally

agreed, and in the end, we had more equipment at front of house

than most of today's studios."

Along with the excitement of making this challenge work,

Guthrie was quite naturally anxious at the prospect of working

in the radically different acoustic environment of the concert

arena, although the pressure was lifted by the luxury of spending

up to three weeks in production rehearsals at the LA Sports Arena.

This followed preliminary routining of the music with the band at

Leeds Rehearsal Studios on Sunset Boulevard (next door to where

Jackson Browne was rehearsing), while the set was assembled and

tested on a movie sound stage in Culver City. "Once the show

started to take shape, the production rehearsals had to take place

in the arena simply because the show was so enormous," says Guthrie.

"I quickly became acquainted with the acoustics of a large room,

albeit an empty one which is another issue altogether. You can

EQ and voice the PA thoroughly but, of course, when the doors open

and the audience pours in, the acoustics change dramatically. This

was particularly evident at Nassau Coliseum, where we played in the

depths of winter and many of the fans were wearing thick sheepskin

coats, which dampened the sound even further. For me though, the

first show would be the first time I would have to deal with this

phenomenon."

ON STAGE

Few bands had dared to even think of staging such an ambitious

show, let alone tried to plan one. Inevitably "The Wall" grew

into a monster, a logistical nightmare which required setting up

specialist teams within the crew to ensure precision -- a procedure

which has since become commonplace within the live industry. The

complex music also determined that each Floyd instrumentalist was

duplicated and the eight-man line-up enhanced by four backing

vocalists, but it was also Waters's idea that the Floyd members

would each have a "shadow" and this was reflected in the positioning

and lighting of the musicians. There was even a "Wall" uniform:

the crew and band alike wore black short-sleeved shirts with sewn-on

"hammer" logos. Everyone, that is, except Waters who chose to wear

a T-shirt with a large "1" emblazoned on his chest. Number One?

Top Man? Big Cheese? It made you wonder.

Waters's vision necessitated two custom-built stages, one in

front of the other at slightly different heights, which were

separated by a large black Duvetyne drape. The task of pacing the

building of the wall between the two stages and isolating the band

from the audience while the show was in motion was no mean feat in

itself. Add to this the operation of the Scarfe inflatables, the

flying pig, a crashing model Stuka, Marc Brickman's imaginative

lighting, film projections, and copious pyrotechnics, and one

begins to realise the intensity that must have built up behind the

scenes while the audiences sat there agog.

All senses were sent reeling from the very beginning of the

show, which began with a quite startling piece of deception.

Despite being introduced as Pink Floyd by a deliberately tacky MC,

the first number, "In The Flesh?" (a satirical nod to Waters's

"Animal" tour experience), was performed at the front of the stage

by the surrogate four-piece (Snowy White, Andy Bown, Peter Wood,

and Willie Wilson), who wore perfectly formed latex Floyd masks

modelled for by the genuine band at the Hollywood film studios

during rehearsals. No wonder the audience was confused when the

second number started and Waters and co. came into view!

HOLD IT! HOLD IT!

Whilst the band and crew had worked solidly on perfecting the

show over the previous weeks, not one complete run-through of

the production had been attempted without being punctuated by some

form of technical or directional problem. Rehearsals continued in

this vein right up until the first night, mostly due to Waters's

relentless perfectionism. It should be noted that the credits for

the show read: "'The Wall' written and directed by Roger Waters.

Performed by Pink Floyd." While Gilmour's role was to rehearse the

band and ensure that individual parts were reproduced faithfully

from the album, Waters's unique position in this whole production

arguably made him the only person who knew exactly how the show

should be run. Given the additional responsibility as a singer

and bassist, one can only imagine the frustration he incurred when

rehearsed sections did not quite go to plan.

Guthrie recalls: "There were so many things to coordinate that

we would get part of the way through, only to be stopped by Roger's

loud voice through the PA saying, 'Hold it, hold it!' He'd then have

a go at somebody for not bringing a puppet out at a vital moment,

or saying that the wall should have been built up more by now, and

there were also numerous occasions when he'd alert us to badly timed

sound effects or lighting cues. It went on and on like this every

day with continuous interruptions from Roger, shouting 'Hold it,

hold it', and we were becoming increasingly frustrated because we

were very anxious to do a complete run-through in order to get a feel

for the dynamic and flow of the show." Despite such wishes, the crew

had to contend with rehearsing in sections which, Waters has said, was

the only way he could accurately plot the progress of his production.

When the big opening night arrived, Guthrie and his front-of-house

team joked before the show that whatever occurred, at least Waters

could not interrupt the proceedings. After all, this was now playing

to a real audience of 11,000 people. But... "During 'The Thin Ice',

I could hear an intermittent electronic crackle. I thought it was

coming from one of the drum mics, and my assistant engineers Rick Hart

and Greg Walsh were going frantic, listening through headphones and

soloing everything in an attempt to find the source of this noise.

We couldn't work out what it was. Then all of a sudden, Roger shouted

through the PA, 'Hold it, hold it!', and I nearly died! I turned to

Rick and could see the colour draining from his face. I thought I was

dreaming. I looked at Greg, and he had already turned white and was

staring in disbelief -- I think we were all in shock! The pyrotechnic

guys had guaranteed that when the plane exploded at the end of 'In The

Flesh', all the flames would be out upon landing at the side of the

stage. But when they raised the drape between the two stages, some

of the embers from the spraying pyros had lodged in the material and

caught fire. The sound that we had been hearing had come from the

riggers in the catwalks above the stage trying to put out this fire

with extinguishers, so it wasn't anything electronic at all!"

Waters remained calm and informed the audience that the show would

resume as soon as the minor blaze was under control and the drapes

were flown back into the ceiling. Adds Guthrie: "Half the fans

panicked and ran to the exits, and the other half were stoned and

thought it was all a pretty far out part of the act! By the time

they restarted the show, I could just about see the stage as the

beams of light shone through the heavy, thick smoke left behind."

Vision later improved as the audience was treated to the heroic

sight of Gilmour, hydraulically lifted above the wall to perform

"Comfortably Numb" [quite possibly my most treasured memory of any

concert I have ever seen]. This scene, according to Phil Taylor,

was included in the show at the express request of Waters. "When

we were rehearsing, Roger decided it would be a fantastic idea if

Dave appeared over the top of the wall for his vocal sections and

guitar solos. He said 'You should go up on a lift and it'll look

great.' I must have been laughing a little too loud, because Roger

quickly turned to me and added 'And you can go up with him!' So

that was me with Dave every night, crouching beside him and holding

on for dear life!"

It is worth noting that the first night in Los Angeles was not

the only instance where Roger Waters was forced to bring an untimely

halt to a show. The previous occasion was in July 1977 during the

band's four night run at Madison Square Garden in New York City on

the "In The Flesh" tour, where it was not fire but a technician's

stupidity which was to blame. Snowy White says: "Because of various

union regulations in the States, we were forced to use a number of

local technicians and one of the lampies didn't have a clue. He was

focusing a spotlight at Roger's feet instead of his face and body,

and Roger reacted by bending down and 'willing' it upwards with his

hand. After a while, he'd clearly had enough of this incompetence

and he stopped the band halfway through a song, saying, "I think you

New York lighting guys are a f**king load of shit!', and we then

carried on without batting an eyelid!"

WALL OF SOUND

Problems with the opening shows in Los Angeles were not confined

to the legendary fire incident. Guthrie's spine tingles at the

memory of receiving a whole consignment of defective Altec 15-inch

woofers, which necessitated brisk replacement with Gauss 15-inch

drivers. However, such recollections pale into insignificance when

reappraising what was arguably the most potent PA system of its time.

Purchased by Britannia Row especially for "The Wall", in addition

to a new Martin quad system, was the new Altec "Stanley Screamer"

grid-flown system designed by Stan Miller, which was dubbed the

Flying Forest because of its array of different sized constant

directivity horns. Those fortunate to have witnessed any of these

magical shows will remember the awesome sensurround experience of

having low register vibrations firing up their spine. The influx of

sensurround movies in the '70s, such as "Earthquake", had inspired

Guthrie to suggest augmenting the PA with a system which would enhance

the show's sound effects.

As well as being placed either side of the stage underneath

the PA, a mixture of 16 Gauss-loaded Altec 2 x 18-inch subs and

(in Europe) an unspecified quantity of 2 x 15-inch Court DLB-1200

cabinets were positioned under seating blocks all the way around

the perimeter of the arena. The cabinets were used in conjunction

with a sub-sonic synthesizer for ultra low sub-bass at several key

points during the show, such as the helicopter buzz on "The Happiest

Days of Our Lives" and the explosive climax when the wall came

tumbling down. Guthrie says: "That was when I pushed the fader up

as far as it would go, and the whole arena literally started shaking.

Anybody lucky enough to have been sitting over those sub-woofers must

have been bouncing!"

LAYING THE FOUNDATIONS

No fewer than a massive, and previously unheard of, 106

unautomated input channels (not including echo returns) were put

under Guthrie's jurisdiction at front of house. Fortunately, his

life was made easier by enlisting the help of assistant engineers

Rick Hart, from the album mixing sessions at Producer's Workshop in

LA, and Greg Walsh. "There were actually four drum kits, because

Nick Mason and Willie Wilson each had a kit on both stages, and we

used a colossal amount of microphones. And because Roger and Andy

Bown both played bass, there had to be two bass rigs on each stage

(two Altec rigs for the front stage and two Phase Linear-amplified

Martin rigs at the rear). So just concentrating on the balance of

the music was enough for me to think about," recalls Guthrie.

Once again at the heart of the mixing process was the famed

UV-lit Midas 40-channel custom board with its central quad section.

The main board, however, underwent significant repair work in

between the 1980 and 1981 "Wall" shows after being damaged in a

fire at Alexandra Palace. Despite the wealth of facilities offered

by the Midas for the "In The Flesh" tour, it could not cope alone

with "The Wall"'s demands for channels, not even with the addition

of a 24-channel stretch. Williams recalls that "we just kept

patching in 10-channel stretch units, ad infinitum!"

To simplify the complex mix, Guthrie devised a plan whereby

Hart would look after the left side of the desk and Walsh, the

right, while he mostly concerned himself with sub-groups in the

middle. This triumvirate engineering formula has since become

a Floyd norm. "They would feed me whatever was playing at the

time. If Dave was playing acoustic guitar, they would make sure

that all of his electric guitar mics were muted, so the only thing

being fed was the acoustic. I had a couple of faders that were

simply for Dave's guitars and I could balance them accordingly.

If I wanted to change the balance between mics, I could just reach

over and do that, then return to my normal balancing act. The same

regime was followed for the keyboards. Rick Hart was also flying

the quad, so when different effects needed to fly around the room,

he was operating the joysticks. Greg, meanwhile, was running the

echo spins."

Added to the outboard racks used for the "In The Flesh" tour

were several items removed from Britannia Row Studios at Guthrie's

specific request. "I just added all the stuff I liked to use in

the studio," he says. "We had Urei 1176 and dbx limiters, Eventide

Harmonisers, Publison DDLs, and for outboard EQ, I used K&H

parametric equalisers. In fact, we pretty much emptied Brit Row

and stuck everything in touring racks." This also followed through

for the microphone inventory. For drums, Guthrie's choice included

an AKG D12 on the kicks, and 202s and 421s on toms, while vocal mics

were both Shure M57s and 58s. One of the first quality radio mics,

a Nady, was also used by Waters as he wandered the stage for a large

proportion of the set.

Hardly surprising for someone of his background, Guthrie

borrowed much from his portfolio of studio techniques for the live

shows and began to work on the front-of-house mix only when he and

the band were satisfied with the sound on stage. "It's my standard

practice in the studio to get the sound right in the playing area

first and then see what I can do to improve on it on the desk, and

I was pleased to discover that it also worked well live." He even

voiced the PA in the same way that he voiced studio monitors, and

for this purpose, he carried with him to each venue a Revox and a

quarter-inch tape of "Comfortably Numb" to play through the rig at

high levels, while he listened around the arena and ran back to

the mixing area to make adjustments on the graphics.

The subtractive EQ techniques for which he had gained a

reputation in his studio career were also adopted for the shows.

He says: "When you're dealing with PA systems which tend to squawk

at you and be a little nasty, it's always a good move to start by

cranking up the volume and subtracting what you don't want to hear

in terms of frequencies. It always sounds more natural and I can

get a much bigger sound that way. You start flat and listen to

what is going on, working out if there is a problem with what you

have and how you are going to rectify it. One should never EQ for

the sake of it, although many people do."

Guthrie's studio experience was further called upon to achieve

maximum separation between the backline amplification in a bid to

improve control. He and backline head Phil Taylor placed large

foam baffles either side of the guitar and bass amplifiers and

keyboard Leslies, almost as if they were establishing a studio

environment on stage. Says Guthrie: "We found that underneath

the stage was a huge area of low frequency rumbling, which was

reducing the definition of the low end, so we hung more of these

foam traps down there at varying intervals and it made an enormous

difference. The other thing we did was to turn everyone down on

stage so the band were playing at an unusually low level. I

thought they would tell me to piss off, quite frankly, but Roger

was actually very supportive, because he wanted to achieve the

highest resolution sound possible. It was a bit of a problem with